Scientific workplaces are not particularly diverse. The underrepresentation of women and people of color in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) has become a field of study in itself, with experimental and observational data demonstrating systematic biases against racial and ethnic minorities applying for grant funding and against women applying for research jobs. This is despite data showing the measurable benefits of diversity in scientific collaborations. Still, there’s a dimension of diversity in STEM careers that we know almost nothing about: sexual orientation and gender identity.

In the last few years, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and other queer-identified (LGBTQ) folks have made big gains in political acceptance and legal support, but we don’t know how many people with LGBTQ identities work in STEM, or how they’re doing. With few exceptions, funding agencies and faculty hiring committees don’t ask about applicants’ sexual orientation, even though questions tracking race, ethnicity, and gender have become standard.

This lack of attention to sexual orientation got under my skin precisely because I’m a gay man, and I’ve found science—specifically, evolutionary biology and genetics—to be a comfortable fit. I know accomplished LGBTQ scientists in my own field, like Douglas Futuyma and Joan Roughgarden; and there are prominent LGBTQ figures in the broader history of science, like Alan Turing, and scientists who broke ground for the gay rights movement, like Frank Kameny. Yet science isn’t seen as a natural career path for people like me in the same way the arts and humanities are. My personal experience is, at best, one anecdote towards correcting that; like any scientist, what I wanted was data.

After several fruitless Google Scholar searches for studies of LGBTQ representation in science, two things occurred to me. One was that many of my questions could be answered with a simple online survey, if it found enough participants. The other was that I had a friend who did exactly the kind of research I was contemplating. So I sent a text message to Allison Mattheis, who studies educational policy and diversity issues, and asked if she thought my survey idea would produce publishable data. Not only did she say “yes,” she agreed to help me put it together.

Studying people is, obviously, entirely different from population genetics research in plants or insects. We could just ask our subjects questions, and they’d give us data! Or so I thought. More than 1,400 folks working in STEM fields, from graduate students to emeritus professors, responded to the survey we posted online, and dozens agreed to record follow-up interviews to give more detail. On the other hand, determining what questions to ask turned out to be complicated—maybe especially so given that we were asking scientists, engineers, and other precision-minded people.

As an example, one of the trickiest questions for any study of sexual orientation and gender identity is exactly that: how to write the question or questions in which people specify their LGBTQ identity. Even though we offered a space to write in any queer identity, we received multiple complaints about the terms we offered in the multiple-choice questions on orientation and gender identity. Our participants being scientists, nearly as many complained about the list of scientific sub-fields we offered for participants to describe their expertise.

Another important issue turned up when we ran a draft of the survey past some scientist friends, and they were unsure how to answer a question asking whether they felt welcome in the workplace. “Welcome” was too subjective for a simple yes or no answer, they thought. So we added an option that the beta-testers found more workable: whether they felt they were treated the same as their straight colleagues. On the final survey, people choosing “welcome” and “treated the same” (85 percent of participants, altogether) described very similar experiences.

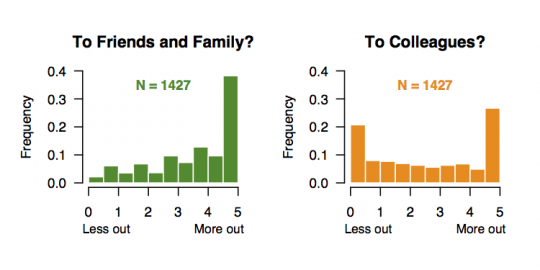

The results of the survey paint an optimistic picture. Fifty-seven percent of survey participants estimated that more than half of their colleagues knew their queer identity. That’s a lot fewer than gave the same rating for their friends and family—participants were much more likely to be “in the closet” in the lab than in the rest of their lives (Figure 1). However, somewhat more of our participants were out to more than half of their colleagues than those who answered a 2014 survey of the entire U.S. workforce.

Figure 1. The degree to which survey participants rated their openness about their LGBTQ identities, on a scale of 0 (“no one knows”) to 5 (“as far as I’m aware, everyone could know”) for friends and family (left) and colleagues (right).

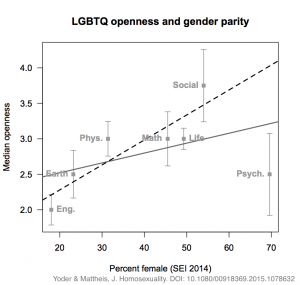

While things may be better in STEM than in other careers, there’s room for improvement. The survey reveals hints about how to make that improvement. Participants were more likely to be out to their colleagues if they also described their workplaces as safe and welcoming, and if their employers provided explicit support for LGBTQ employees, like recognizing same-sex partners or making sure trans-specific healthcare is covered by company insurance. Participants were also more likely to be out at work if they worked in STEM fields with greater representation of women (Figure 2). Maybe workplace diversity is non-additive: fields that have a wider variety of perspectives and experiences to begin with may be more open to new kinds of difference.

Figure 2. Survey participants in STEM fields with better representation of women reported greater openness to colleagues. Points give median ± 95% CI of openness ratings for each field. Solid line: regression for full dataset (p = 0.31). Dotted line: regression for all fields except Psychology, where considerations in clinical settings often preclude discussion of personal information (p = 0.02).

We were repeatedly overwhelmed by the support of the scientists, engineers, and educators who opened up to us about their experiences. One postdoc wasn’t out to colleagues because no one in their department talked about their personal lives for fear of appearing insufficiently committed to science. A professor who had changed institutions several times had to think about how her wife would be treated on each new campus. Trans men and women had undergone gender transition in graduate school—with and without departmental support for basic things like changing their names on official records.

That may be the most important difference between this project and my day-to-day research. In the end, the statistics summarizing the survey are composed not of replicates in a growth chamber, but hundreds of individual human lives. We’re grateful to everyone who shared their stories, and we hope our analysis can help make science a more welcoming place for everyone.

Jeremy Yoder is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow studying the population genomics of local adaptation and coevolution in the Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences at the University of British Columbia. The Queer in STEM project is supported by the National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals.

Jeremy Yoder is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow studying the population genomics of local adaptation and coevolution in the Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences at the University of British Columbia. The Queer in STEM project is supported by the National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals.

| The views expressed in guest posts are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Genetics Society of America. |