As a geneticist, when I get asked by a friend or neighbor to explain what I do for a living more than just being a biologist, I might say something like: “I work on understanding how proteins function using yeast and other model organisms.” Besides that look of incomprehension that suggests I may have absent-mindedly switched over to speaking Tibetan, my companion’s expression betrays the questions: “With all your years of being a scientist, why aren’t you doing something useful? How come you’re not finding new drugs active against cancer cells? Or learning why brain cells degenerate in Alzheimer’s disease? Or at a minimum, figuring out whether I will lose more weight on a diet of only protein, or only fat, or only high fructose corn syrup?” How can we productively engage with our fellow citizens about science so they understand not only what we do, but also why we do it and why they should care?

As a geneticist, when I get asked by a friend or neighbor to explain what I do for a living more than just being a biologist, I might say something like: “I work on understanding how proteins function using yeast and other model organisms.” Besides that look of incomprehension that suggests I may have absent-mindedly switched over to speaking Tibetan, my companion’s expression betrays the questions: “With all your years of being a scientist, why aren’t you doing something useful? How come you’re not finding new drugs active against cancer cells? Or learning why brain cells degenerate in Alzheimer’s disease? Or at a minimum, figuring out whether I will lose more weight on a diet of only protein, or only fat, or only high fructose corn syrup?” How can we productively engage with our fellow citizens about science so they understand not only what we do, but also why we do it and why they should care?

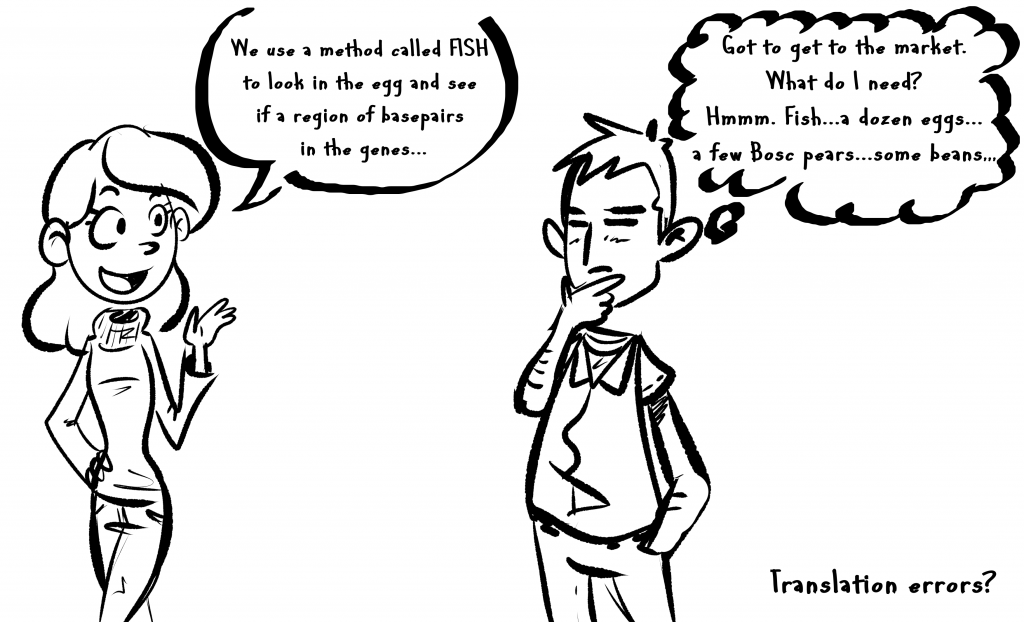

It’s likely that you’ve faced similar situations yourself when you casually mention at a party that you study how wings develop in a fruit fly, or how a tiny roundworm responds to being poked, or what happens to gene activity in a plant when it’s suddenly warmed up. We might think these conversations are hopeless, conveying no more subtlety than describing delicate flavors by pointing to photographs of food in a restaurant in Japan. The worst possible interaction – and unfortunately an all too common one – might be our own look of incomprehension that someone could be so clueless about science.

But such a reaction is not helpful to the cause of keeping research funding a priority, as we rely on the support of citizens for a share of tax dollars. Plus, you never know when the person you’re chatting with seated next to you on a plane is your local Congressional representative or the assistant to the newly-minted Jane Q. Billionaire, who is looking for a good cause to invest some of that windfall from her recent public offering.

If it’s impossible to convey the intricacies of biology in a few moments of conversation, what should we attempt to get across when we talk to non-scientists? At the least, we should try to transmit the idea that for a disease like cancer, better treatments come about only when biologists better understand processes like how genes suffer mutations and how cells divide – and that we gain most of this knowledge from studying simple organisms.

We need to mention that bacteria, plants, fungi, animals – the whole gamut of life – operate in many ways just like human cells, because all of life evolved from the same primordial cells. That the basis of the biotechnology industry is a bunch of proteins discovered in bacteria and repurposed for practical uses. That the field of genome editing, increasingly in the news, relies on reagents discovered by studying how bacteria resist viral infections. Maybe this conversation then steers in the direction of what genes are, what cells are, what evolution means – and you start to convey some of the most basic principles of our field.

But if we can’t explain the real science we do at the level of even high school biology, how helpful is it to engage in these conversations? One reason to get comfortable talking to the public about your work is that many Americans can’t name any living scientist, and don’t know that scientific research is being carried out in their city. But after your conversation, your friend should be able to name you and your institution. In fact, at a meeting of nonprofit society leaders I asked someone who leads an organization of members in the bridge and tunnel business this very question: “Can you name a living scientist?” He looked down at my name tag and said: “Stan Fields.”

As another reason to engage with the general public, the passion in your voice and the excitement you exude for doing research will be heard and felt. Your friend or traveling companion will come away impressed by your energy, and thinking perhaps that the notion of investing tax dollars in you is not a bad one. Your discussion may engender some small appreciation of why biologists work on the organisms we do. And maybe your friend has a young son or daughter interested in science whom you might encourage with a volunteer position or a day spent in a lab.

Let’s keep the dialog going with our fellow citizens. It shouldn’t be difficult. It’s not rocket science, it’s not brain surgery: it’s just genetics.