Today’s guest post was contributed by Caitlan Rossi, a scientific and medical writer. Her work can be found at caitlanrossi.com.

“The first step is getting a student in front of a microscope and pipette,” said Jason Williams, Assistant Director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) DNA Learning Center. Through a unique blend of education, outreach, and empathy, Williams specializes in teaching bioinformatics and data-driven science to learners of all skillsets. His curricula have taken root internationally and at the center’s locations in Puerto Rico, Nigeria, and China, endowing hundreds of thousands of students and educators with a passion for the human genome.

The Johnny Appleseed of genomics

Jason Williams’ career began at the bench on the main campus of CSHL, where he first studied the molecular genetics of plant development in Arabidopsis before shifting his focus to prostate cancer. Four years later, an opportunity arose at the CSHL DNA Learning Center, the world’s first science center devoted to public genetics education. Having grown up in Long Island and attended the center himself in high school, Williams saw an opportunity to pursue a deeply rooted interest in teaching. “I really enjoyed some of my previous educational experiences and have had some creative teachers. This was my chance to do something I’ve always wanted to do,” he said. “And I’ve been doing it ever since.”

Now, Williams likes to think of himself as the Johnny Appleseed of genomics, a role he understands as a tremendous privilege. “Most of my teaching does not happen in this building anymore,” he shared from his office in Cold Spring Harbor. “Most of my lessons are designed for other people to use. I take whatever seed I can leave behind and it grows in different ways because students know their context. Dropping off DNA Sequencers (which come in the mail), watering it with a group, and saying, ‘see you later’,” he explained. For Williams, the most rewarding part of this outreach is seeing those seeds flower: a researcher whose thesis got accepted, a student who assembled their first genome.

Translational skills

Williams is drawn to translation—making complex topics accessible to different audiences. He works closely with high school students, science teachers, and geneticists alike. Sometimes he’s introducing genomics to beginners; other times, he’s helping early-career researchers or PIs develop computational skills despite never having coded before. Williams believes there’s always an element of personalization in the learning experience, no matter the level. “It’s very much about empathy and understanding where they may be coming from, and how you need to build a scaffold particular to that audience to get them where they want to be,” he shared.

Genetics is for everyone

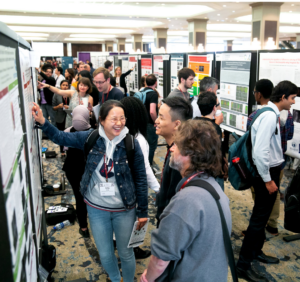

The DNA Learning Center is the largest provider of pre-college biotechnology education in the country. To Williams, what’s special about genetics is its universal familiarity: we can all recognize the famous double helix representation of DNA. “It’s an iconic thing that people relate to and understand. There’s no way I can’t connect a topic to something you see or do every day,” he said. “We have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to ways to reach students—we just have to try our best to understand where the student is at and where they’re coming from,” Williams added.

Indeed, there’s a certain multidisciplinary accessibility to genetics that separates this study from other sciences. “Where we are privileged in genetics and DNA in a way that many other topics might not be is that a student can basically do just about everything a researcher can do,” Williams explained. In nuclear chemistry, for example, hands-on experiments may be out of reach. “But in genetics, the basic fundamental tools of the trade, from Mendel and pea plants that can be found in a garden, to now sequencing DNA…there’s not much fundamentally out of reach for a student to try their hand at,” he elaborated.

Unlocking motivation

Williams believes in learning about students before attempting to teach them. Reading the classroom, he noted, requires more than just scanning the faces in front of you. “Drowning doesn’t always look like drowning. Being sensitive to that and creating opportunities for people to convey where they’re at—those are skills that come from having done it a lot of times and seeing where things tend to go wrong,” he explained.

In addition to his work with the DNA Learning Center, Williams teaches science classes at the Yeshiva University High School for Girls in Queens. When it comes to the elusive task of motivating students, he believes in making science personal. “When I am in front of a classroom, I tell students at the beginning of the year, I’m much more like the bus driver. I’m going to drive you to many, many different places but it’s really up to you to get out and explore,” Williams shared.

Above all, Williams wants students to make the science their own. “We have the responsibility as educators to bring the power of understanding into people’s everyday lives. I would make that argument as hard as I can make it. Letting them see and letting them do and letting them ask as many questions as they have—that centers them around the science rather than a voice from up high in a white lab coat telling them what to do. Science education is a much greater responsibility now than it has been before,” he emphasized.

Please join us in congratulating 2025 Elizabeth W. Jones Award for Excellence in Education recipient Jason Williams on his significant and lasting contributions to genetics education.

2025 GSA Awards Seminars

Join Jason Williams on July 10, 1:00–2:00 p.m. EDT. Genomics once required international research consortia. Now, high school students can sequence genomes. In this seminar, Jason Williams, Assistant Director at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory DNA Learning Center (DNALC), will discuss how DNALC tools and networks help bring DNA sequencing into the classroom—and why doing so is an urgent and effective way to build the STEM workforce.