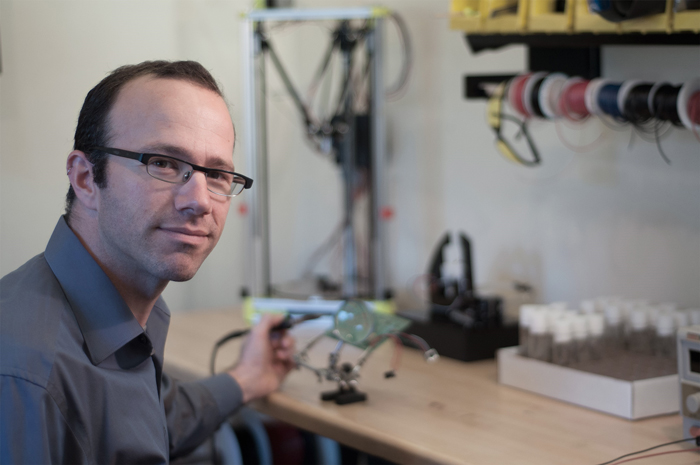

Dave Zucker, founder of startup FlySorter, talks about treating new positions as training, and how he builds his own community of colleagues from different fields.

Dave Zucker, founder of startup FlySorter, talks about treating new positions as training, and how he builds his own community of colleagues from different fields.

In the Decoding Life series, we talk to geneticists with diverse career paths, tracing the many directions possible after research training. This series is brought to you by the GSA Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee.

How have your life experiences shaped your career?

I have an undergraduate degree in physics, but knew it was not something I wanted to pursue long-term. When I graduated, it was the tail end of the first dot-com boom, and it was a great time to say you were a programmer and get a job. I had some experience coding, and I started working for a company that made autonomous underwater vehicles designed to survey an area of the sea floor. Part of the job was going on brief expeditions and working with the robots. Even though it was the coolest job I could imagine in software, it was not fulfilling for me. I remember building shelving racks for servers one day and felt so much more satisfied doing that rather than programming. I realized there was a problem!

I asked the company if I could be an intern at the mechanical engineering department. That started the next phase of my career, where I worked in mechanical engineering and product design for the last 15 years.

What does a typical day at work look like for you?

FlySorter is a one-person shop at the moment. I am doing everything including prototyping new tools, designing parts, manufacturing, administration, web development, and marketing. There are about eight to ten different typical days, and one of the nice things about that is that if you don’t want to do a particular task that day, there is a huge list of tasks that you can do in the meantime. It’s the blessing and the curse of having a small business.

What are your favorite tasks?

I still enjoy putting things together. All FlySorter products are assembled in our office/lab, and I find that very satisfying. I have a 3-D printer in the lab that accelerates development so much! I can come up with an idea, create the file and hit print; fifteen minutes to two hours later, I get a physical part! That makes me feel like we live in the future.

Another task I really enjoyed was attending the GSA fly conference. This was the first year I had a booth, and it presented hundreds of opportunities to talk with researchers about what they are doing and what they want help with.

What are your least favorite tasks and how do you find the motivation to tackle them?

There are things that come less naturally to me, and those are always tasks that I put off for a long time. I am not naturally a salesperson, and tasks like financial book-keeping or marketing take a lot of energy for me. I wish I had a trick that always works!

Because it is such a small company, I try to set up lunches, coffees, or beers with friends. I’ve effectively made myself colleagues with people from very different industries. I have some folks who are engineers, and we nerd out about design details. I also have connections with people in business or sales/marketing, and I find that talking to those folks and asking them for their tricks about how to do these things gives me motivation and energy to go through it.

Working by myself is one of the things I like least about my job right now.

What’s the most surprising aspect of starting your own company?

Dave and his wife Dina enjoy traveling together all over the globe. Here, they are in Florence, Italy

It’s human nature to feel that the things people say are universal don’t necessarily apply to you! When you start a company, people will say, “It’s really hard, and you need to think about whether it’s right for you, and there will be down times.” It’s easy to think, “Oh, I understand, but that’s not what is going to happen to me.” But sure enough, there have been really tough times. It’s hard to know how things are going to affect you until you try. There have been a couple of stretches where I was depressed about how my work was going. It’s hard to recognize that for yourself, and my wife is great at pointing out when things are not good and asking me what I can do differently to improve the situation. I think those times were a lot more intense than I thought they would be.

How do you effectively communicate your expertise to a person who is an expert in another field?

Listening is just as important as talking. Being clear that you are knowledgeable in some fields, but not an expert or knowledgeable in other is important. I’m very upfront with people that I am not a biologist.

What are the most important preparations you should make before reaching out to an employer?

I like to do my due diligence and learn about the company and position through Google, LinkedIn, and Twitter to try to understand what perspectives or experiences the person on the other end may have.

A second piece of advice is to treat interviews as going both ways. You’re there to interview them, as much as they are you. Shifting your thinking about interviews so that it is less about giving them all the power and justifying your existence is very helpful. There are a lot of books about interview tactics, but you are there and you are valuable. You want to make sure that this is a good fit, rather than just proving your worth. You can focus on trying to choose positions and organizations that will be good for you. What is good for one person is different from what is good for another.

Lastly, it’s important to think about what you may get out of a particular job. I worked at Microsoft for four years developing keyboards and mouse products. Do I care passionately about keyboards and mice? Not really. Did I learn a phenomenal amount? Yes. It was like doing a Master’s in Engineering, and I was exposed to factories and started to understand what the implications of my design decisions were. I got a huge amount out of that, and when things got repetitive, it was time to move on. There are many things you can take from a job, and it’s great if you can identify that ahead of time.

Dave Zucker unveiling one of his creations, the robotic bartender Sir-Mix-a-Bot http://dsz123.net/Projects/RobotArm/

What does your ideal clock look like?

My ideal clock would bend time so there’s more of it! There are so many things that I want to try, and it just feels like there is not ever enough time. The flip side is, you want to appreciate what you are doing, so maybe my ideal clock is where you can hide some of the hands some of the times. There are times when you want to ignore the fact that there are seconds ticking by, where you can look at the years to get perspective. Then there are times when you want to ignore those bigger time scales. I want all the hands but want to choose which ones show up.

About the author:

![]() Didem Sarikaya is the Co-Chair of the Early Career Scientist Career Development Committee and an FRSQ Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California Davis. She is committed to bringing forward stories and tools for trainees to learn more about career options so they can develop personally meaningful career trajectories.

Didem Sarikaya is the Co-Chair of the Early Career Scientist Career Development Committee and an FRSQ Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California Davis. She is committed to bringing forward stories and tools for trainees to learn more about career options so they can develop personally meaningful career trajectories.

Learn more about the GSA’s Early Career Scientist Leadership Program.