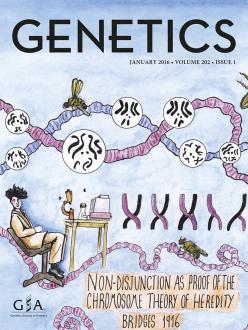

The January cover of GENETICS commemorates the journal’s 100th anniversary and the 1916 publication of Calvin Bridges’ proof that genes lie on chromosomes. The artwork was created by Alexander Cagan, a graduate student at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology studying the genetics of domestication in rats. We spoke to Alex about the cover, his art, and his family tradition of genetics.

We love the January cover! Can you tell us a bit about what it represents?

I tried to encapsulate as much of the process behind Bridges’ work and his 1916 paper as possible. So that started with the Drosophila melanogaster, then the polytene chromosomes, the karyotypes, and finally Calvin at his desk with his binocular microscope figuring it all out. The composition has all these elements floating together, sort of how I imagined the inside of his mind might have looked at the time, full of images of fruit flies and chromosomes!

What was your process for creating the image?

I started out by reading Bridges’ paper and researching his life and career to establish the central motifs for the image. As it was for the cover and needed to be a high quality image I chose to do it with traditional pen, paper and watercolors, as I find this gives me a higher level of control and detail than when I work digitally. I drew it in a comic-book style as I think this is a good way to make a bold image that conveys a story but is not the way most people are used to seeing scientific information presented.

Did you learn anything interesting?

I found reading a paper from the beginning of modern genetics fascinating. Learning about the steps he took, the careful observations and experiments needed to figure out what we now take for granted now, was great. It was almost like reading a classic detective story. There are so many papers being published all the time that as a grad student it often feels hard to stay on top of it all. This experience definitely made me think that it’s worthwhile going back to foundational papers to better understand the history of the field. I think it’s easy to forget what genetics was like before the age of genome sequencing.

While researching Calvin’s life I also learned that he was a pretty colorful character. Apparently in his later life he designed and built his own futuristic sports car called the lightning bug.

We invited you to create the Bridges cover after we saw your sketches of conference presentations and papers on Twitter. What inspired you to start drawing science abstracts?

I’ve always enjoyed drawing, particularly sketching. I’ve been doodling in the margins of my notes since I was at school. My mum, who is a set and costume designer, has always encouraged me to keep up with drawing and try to find ways to use it in my work. The drawing at conferences began when I went to a conference with an iPad and a Twitter account. I had no prior plan to draw the talks. I was following the conference on Twitter while I was there, which was great for keeping up with all the parallel sessions. I think about halfway through the conference I realized that I could perhaps contribute to all the tweeting with my notes if I just modified the way I took them to make them a little more legible to others. It was also a way to circumvent Twitter’s 140 character limit! Fortunately people seemed to appreciate them and so I kept going with it.

A new hypothesis is proposed to explain the 'domestication syndrome' observed in mammals, by Wilkins et al. pic.twitter.com/Kle437irax

— Alex Cagan (@ATJCagan) July 28, 2014

What’s your process for the conference sketches? How on earth do you create them while also paying attention to the talks and dealing with general conference overstimulation?

The secret is drinking lots of coffee during the breaks. I’m still experimenting with it and trying to find the best way to present the information from talks in an engaging and informative way. If I know I’m going to be attending a series of talks in advance I usually prepare the titles and names of the speakers for each sketch before, as every second counts during the standard 10-15 minute conference talks.

During a talk I go back and forth between sketching the speaker and writing down the key points of their presentation. Rather than finding that sketching distracts from paying attention during a talk I actually find that it helps. When you have such a short space of time to put together a coherent sketch you have to stay focused. Trying to include only the key features of a talk means helps me to try and digest it. Also as I’m used to doodling in the margins it’s not that different from my usual note taking process!

Bachtrog on the good, the bad and the ugly of transposable element evolution #smbe15 pic.twitter.com/I5yuVeHOm6

— Alex Cagan (@ATJCagan) July 16, 2015

Do you have any favorites among the Twitter sketches?

Hmm, tough question. Practically speaking the keynote talks at conferences tend to be the most fun to sketch, primarily because they last an hour, which isn’t that long but feels like a gift in comparison to most talks! Though I have to admit the challenge of sketching a talk in ten minutes can be pretty fun.

Does art play any other roles in your science life?

I really enjoy looking at old scientific illustrations, such as Robert Hooke’s drawing of a flea in his book ‘Micrographia’, D’Arcy Thompson’s drawings of organic shapes in ‘On Growth and Form’, and of course all of Da Vinci’s sketchbooks. They are part of what inspired me to go into science. However finding ways to incorporate art into my own research, which is in the field of population genetics, is more challenging. Although there are certainly some elements of population genetics that have a very artistic feel to them, such as fitness landscapes. I’m fortunate to spend some of my time working on animal behavior, which does provide great opportunities for sketching as a tool to aid observation. I think there are still ways to incorporate art into my science that I haven’t discovered yet, but hopefully they will come.

What about art in your “non-science” life?

Yes, I try to draw quite often when I can find the time. For me it’s a great way to relax, which I feel is an essential survival skill for a life in science.

Cranial appendage diversity in ungulates is incredible pic.twitter.com/dLC9WUOzlI

— Alex Cagan (@ATJCagan) June 14, 2015

I hear you’re a descendent of Sewall Wright, 1934 GSA president, one of the founders of population genetics, and skilled guinea pig experimentalist. So I guess there’s a family tradition of rodent genetics! Did he inspire you to pursue evolutionary genetics or was it pure coincidence?

Yes that’s true, he is my great grandfather. It was a pure coincidence that I also ended up developing an interest in population genetics. I had planned to become a social anthropologist but got seduced by biological anthropology courses during my undergraduate degree. It was only once I had already developed a strong interest in genetics that I became aware of the role Sewall Wright played. I was born the year before he passed away so it is a lovely benefit of being in the field that I get to hear stories about him from people who knew him who are still working and I always enjoy that.