Nadine Piekarski, an embryologist at The Fertility Center at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), describes her experience transitioning out of academia and how she uses skills from her PhD training in an IVF clinic.

Nadine Piekarski, an embryologist at The Fertility Center at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), describes her experience transitioning out of academia and how she uses skills from her PhD training in an IVF clinic.

In the Decoding Life series, we talk to geneticists with diverse career paths, tracing the many directions possible after research training. This series is brought to you by the GSA Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee.

What has influenced your career decisions?

I was interested in biology, and it came easily to me. Starting from my undergraduate research, I followed a straight path of academia; everything seemed to fall into place. I am from Germany and did my diploma and PhD there at the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, focusing on embryology, development, and evolution in Professor Lennart Olsson’s lab. I was developing a system for embryonic fate mapping in a type of salamander called axolotl. Toward the end of my PhD I presented at a conference and was offered a postdoc to continue my research at Harvard in the lab of Professor James Hanken. I had always thought I would become an academic, but during my postdoc I started questioning that path, and the idea of pursuing a different career hit me really hard. Academia can be a stressful and unsteady lifestyle. I felt like I had an open-ended position and did not know where I was going to be in the future. I could not imagine doing this for my entire life. I was also driven by wanting to do something that felt more personally meaningful. Now as an embryologist, I am using similar skills as in my PhD to help families have babies. I make families happy and I get these wonderful, heart-warming thank you cards!

How did you decide on a career in embryology?

It was difficult figuring out what I wanted to do. I felt like my training didn’t explain alternatives to academia, and there wasn’t a straightforward way to get there. The main thing I struggled with was evaluating what skills from my PhD were useful for a job. I realized that if I can do micro-surgeries on salamander embryos, I can probably do it on human embryos. Embryology is a pretty unusual career and you need luck and good connections to get in. Another difficulty was that the entry level for embryology positions is a Bachelor’s degree, and I appeared to be overqualified. I needed to be extra convincing that I really wanted to do this job. Finally, about nine months after my postdoc I was fortunate to get the right contact in an IVF clinic to get my first job.

How have mentors been helpful in transitioning to a new career?

I think that friends, and especially my husband, have been more helpful than official mentors. I have a really good circle of friends; a lot of them are academics, but many have careers in other fields. We help each other, and I am able to ask personal questions about my career and discuss it with them easily. We also provide emotional and mental support. I am relatively new to the field of IVF, so currently I am trying to learn as much as possible from my colleagues. Some of them are pioneers in the field who have been doing IVF since almost the beginning in 1977.

What skills are valuable for this career?

You need the ability to be extremely focused and very dependable, and you definitely need to have very calm and steady hands. Because all of the procedures involve teamwork, it is important to be able to work with people in a team setting. As new techniques and methods are developed, the field can change quickly. For example, many labs had to hire and train people recently to accommodate increases in requests for embryo biopsies and genetic screening of embryos. If you have a PhD, you can qualify to become a High-complexity Clinical Laboratory Director (HCLD), which creates additional career opportunities as a lab director in all kinds of clinical labs.

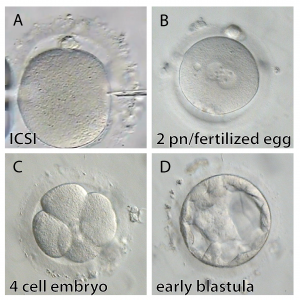

What does a normal day look like?

In a normal day, lab work starts at 7 am. First in the morning is grading embryos, egg retrieval from patients, and sperm preparation for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intrauterine insemination (IUI), all in parallel. Then there are many more different procedures all throughout the day, such as embryo transfers, thawing embryos, freezing embryos, embryo biopsies, and semen analysis. The procedures follow a strict schedule that is tied in with the appointments of the patients. Depending on the volume it can get quite stressful, and you have to stay calm and focused to get everything done in a timely manner.

How do your experiences in your current position compare to the previous positions you held?

As a graduate student or postdoc, I took work home all the time, and there was no downtime. Or I would take downtime and feel guilty. With my current job, I do my work in the lab and then come home and do not have to worry about it. It is still stressful and a lot of work—but in a different way. It is more stressful with respect to responsibilities, and that you cannot make any mistakes. You have to be highly concentrated and very dependable. It’s very different from what I did before, where if an experiment did not work, I could just do it again next week. That will not work now.

I never anticipated having a position in a hospital, but I feel very good here. Often, I talk to other people about my work, and sometimes they say, ‘I had a baby with IVF, thank you so much for what you are doing.’ It is a very rewarding career and makes me very proud and happy to be doing what I’m doing.

About the author:

![]() Caitlin McDonough is the Co-Chair of the Early Career Scientist Career Development Committee and a PhD Candidate in the Center for Reproductive Evolution at Syracuse University. She endeavors to highlight the varied experiences of scientists and make careers in science accessible to individuals of all identities.

Caitlin McDonough is the Co-Chair of the Early Career Scientist Career Development Committee and a PhD Candidate in the Center for Reproductive Evolution at Syracuse University. She endeavors to highlight the varied experiences of scientists and make careers in science accessible to individuals of all identities.

Learn more about the GSA’s Early Career Scientist Leadership Program.