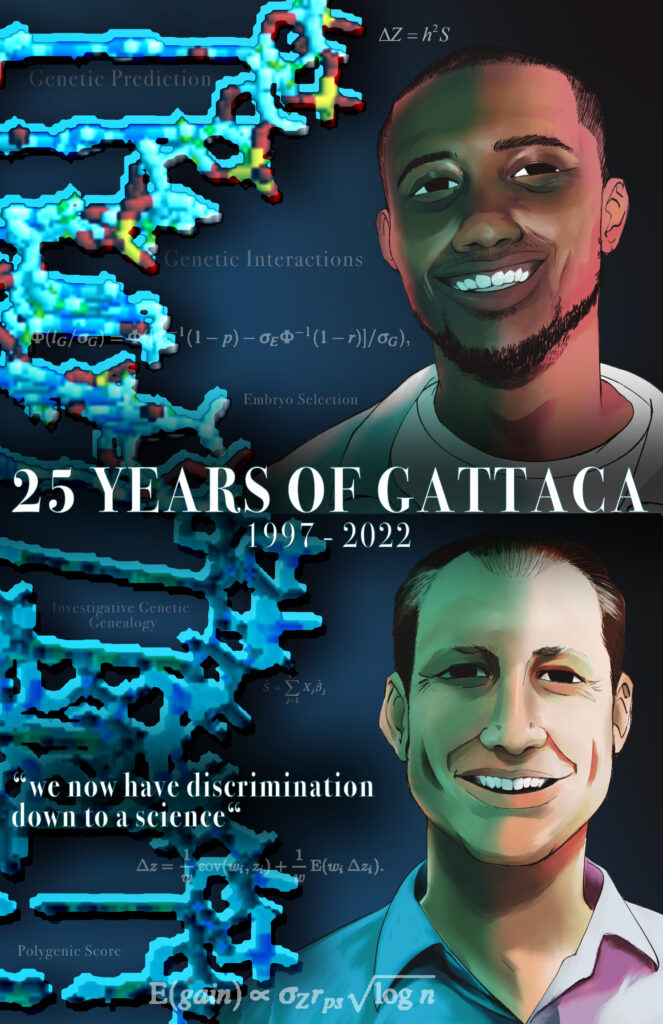

Authors Doc Edge and Brandon Ogbunu discuss their new Perspectives article, which uses the film Gattaca and its 25th anniversary as a framework for discussing societal fears about genetic science.

Why were you motivated to write this kind of paper?

Doc Edge: Brandon and I were at a small scientific meeting in Santa Barbara last spring, and he approached me with the idea to write this piece. I actually hadn’t really seen the movie at the time; I remember my AP Biology teacher putting it on one day after the AP exam, but I don’t think I paid much attention. Brandon might have been disappointed in me for being uncultured, but I went home and watched it, and I knew immediately that I wanted to write about Gattaca. I realized that so many of the things I care most about in my research and teaching show up in this movie in one way or another. In my research, I’m interested in complex trait genetics and in forensic genetics. I also teach research ethics, and in all my classes—even my statistics and genetics classes—I make sure students learn something about the history of eugenics. It’s all there.

C. Brandon Ogbunu: Oh, this one goes back. I first saw Gattaca during my first year in college, and it had a very large effect on me. It was absolutely my introduction to thinking about issues at the intersection of genetics and society. Since then, I’ve always wanted to engage this topic in a formal, technical way. In some ways, my education over the past few decades has prepared me for this.

I think the meeting at The Foundations Institute in Santa Barbara, called “Reimagining the Central Dogma,” was the perfect place to crystallize these sorts of ideas. The workshop had several leading thinkers speak on issues related to genetics, genomics, and evolution, and we had this rich conversation about many aspects of what we are missing from classical depictions and interpretations of the central dogma. The joke is that Doc and I were stuck having lunch together one day, and I introduced the concept of thinking about the film from this lens. On the long drive to the airport, we really began to flesh out the idea for a paper.

How would you describe the collaboration?

Doc Edge: I’ve admired Brandon’s writing from afar for a long time, so it was a privilege to be able to work with him. At the beginning of any collaboration, there is a period when you wonder whether it’s going to work, but in this case that period was short. We had a call where we talked through the points we wanted to hit, and then we really flew—we had most of our first draft within days. Brandon is a really generous collaborator, and I’m grateful he wanted to write this with me.

C. Brandon Ogbunu: Doc is truly one of the best young population geneticists that I know. I’ve seen his work and even taught from his new statistics textbook. What inspires me about Doc is his combination of domain knowledge, technical acumen, and understanding of how the world works. He was someone I could talk to about all aspects of the project. In particular, Doc’s work on molecular forensics piqued my interest. I saw him give a stellar talk on the topic, and I knew then that I wanted to work with him on something having to do with science and society at some point. And we found our calling on this film. It’s been a joy.

What is your general take on modern genomic technologies like facial reconstruction and polygenic embryo selection?

Doc Edge: I’d distinguish modern genetic technology in general from the specific examples mentioned. Genetic technology in general is full of amazing achievements, like modern sequencing and CRISPR gene editing. But in any situation where there is a strong desire for a technical fix to a complicated problem, there is a danger of acting too hastily or overselling—even when all actors have the very best intentions. I feel like my role as a geneticist is to try to figure out what is possible now and what might be possible in the future—and importantly, to do my best to think through some of the implications and state them as clearly as possible. The conversations are bigger than me and require expertise beyond what any one person has.

C. Brandon Ogbunu: Correctly, we tend to separate the ethical issues from the technical ones. That is, whether we should embrace a new technology is its own discussion. But what I often say is that sometimes the technical is the ethical. A lot of these technologies, that institutions and people are eager to put into action, are based on false promises with huge technical and scientific challenges. For example, polygenic scores are a powerful new tool to determine risk for certain complex phenotypes. But are they loaded with so many caveats that their general use for embryo selection cannot be justified.

Are you a fan of science fiction? What are some of your favorite stories?

Doc Edge: I’m inclined to say something like “as much as the next person,” but that’s probably only true if the next person is a huge nerd. I don’t go to conventions or anything, but I do enjoy sci-fi. Last year I read Le Guin’s The Dispossessed for the first time and really enjoyed it.

C. Brandon Ogbunu: I’d say that I’m somewhere between a fan and a superfan. As in: I don’t quite go to conventions and subscribe to zines, but I read many novels and have watched many films. My love of science fiction is a nontrivial part of my identity.

As far as favorites…there are so many. I’m especially inspired by Black science-fiction writers like Octavia Butler and Samuel Delaney. But I embrace other classics, like the works of Ursula LeGuin, Frank Herbert, and Phillip K. Dick.

And leaving books, I confess that I’m a fan of the big franchises like Star Wars and Star Trek. But one of my hobbies is to find random weird science-fiction that speaks to me. For example, Fantastic Planet is a relatively obscure French animated science-fiction film that I love. I think different cultures and corners of the world have interesting things to say about society and the future.

What do you think about the bridge between science and science fiction?

Doc Edge: I’m not sure how to answer in general, particularly given how diverse the approaches to science within sci-fi are. I’ll say that in my favorite sci-fi, the science being fictionalized might be interesting in itself, but the point of it is to expose something about our own world. That’s certainly true of Gattaca.

C. Brandon Ogbunu: The “science” in science-fiction has always been a tricky one. Like we suggest in the paper, science-fiction doesn’t need to be technically accurate to be a very effective piece of work. I find that when scientists criticize science-fiction on technical grounds, they are mostly missing the point. Of course, there are instances when the scientific errors are so egregious that it creates a plothole, but this is usually not the case. And I think scientists should embrace the fictional world as an experimental playpen for ideas that are too risky or bold to test in the real world. I think Gattaca was an example of this done very well. Our new work demonstrates what happens when art decides to explore ideas that society isn’t mature to grapple with yet. My hope is that this interface between science and popular culture is something that grows.

References

Gattaca as a lens on contemporary genetics: Marking 25 years into the film’s “not-too-distant” future

C Brandon Ogbunugafor, Michael D Edge

GENETICS 2022 iyac142; https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyac142