Guest post by Michele Markstein and Gregory Davis.

A summary of the May 26, 2020 TAGC 2020 Online workshop, “Raising a Woke Generation of Geneticists: How and Why to Include Eugenics History in Genetics Classes.”

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder by Minnesota police officers, the nation has been wrestling with how to identify and combat systemic racism. As geneticists, it is clear that our field has much work to do, as we have an appallingly small number of Black geneticist colleagues. As solutions are discussed and implemented at the levels of departments, schools, and professional societies, there is a step forward that we can take right away as teachers of genetics: we can include the history of eugenics in our classrooms. This can make our classrooms more inclusive and our discipline more inviting to people it has traditionally alienated. Additionally, teaching eugenics history can help our students learn to combat racist ideology cloaked as “science,” and it can make the next generation of geneticists less likely to repeat the racist mistakes of our past.

If you do not feel equipped to teach eugenics history, you are not alone. It is conspicuously absent from modern genetics textbooks. For this reason and with the support of the GSA, we convened a virtual workshop at the TAGC2020 conference titled, “Raising a Woke Generation of Geneticists: How and Why to Include Eugenics History in Genetics Classes.”

At the workshop it became apparent that many geneticists who are interested in teaching eugenics history shy away from it for two common reasons: (1) they do not feel qualified to teach history, a subject outside their field, and (2) they do not want to risk creating an uncomfortable classroom environment.

We therefore offer the following advice to help you get started:

- If you are apprehensive about teaching outside of your field of expertise, invite a colleague from across campus to give a guest lecture. Most likely there will be an expert in eugenics history in departments of African-American studies, anthropology, history, legal studies, sociology, and women and gender studies. This is a great way to forge an interdisciplinary relationship on your campus and can be a lot of fun.

- If you are worried that you cannot navigate “uncomfortable” conversations, don’t worry, there are some simple steps you can take to help everyone in the room. First, everyone in the room does better when there is a reminder at the start that conversations about eugenics are likely to bring up uncomfortable feelings in different ways for different people and that this is OK. Second, students tend to be their best selves when ground rules or guardrails are specified to remind them that we are in this together and that everyone is expected to treat one other with compassion, empathy, and respect. For more tips on creating an inclusive environment, we recommend guidelines from Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching: “Teaching Race: Pedagogy and Practice.” Another helpful article was recommended by participants at the meeting: “Signaling inclusivity in undergraduate biology courses through deliberate framing of genetics topics relevant to gender identity, disability, and race” by Karen Hales.

Additionally, we welcome you to download all the materials from the workshop: a list of recommended resources on eugenics history, a summary of participant survey responses, and panelist slide decks as summarized below. We look forward to the community’s continued interest and work in the field, and a future in which teaching eugenics history in genetics is as commonplace as teaching Punnett squares.

Summary of workshop materials:

- A list of recommended resources compiled from panelist and participant input: If you need to catch up on the history of eugenics, take a look at the recommended resource list. A good place to start is with the 10-minute clip from the Ken Burns PBS documentary, The Gene–an Intimate History, and the 3-minute trailer for No Más Bebés by Renee Tajima-Pena and Virginia Espino which documents non-consensual sterilizations of Mexican immigrants in California. In addition, the list has links to lesson plans, websites, videos, podcasts, articles, and books that delve into to the history of eugenics.

- Results from the Workshop Survey: A summary of participant advice, concerns, and recommendations for the future. The entire set of survey responses is included.

- Panelist slide decks:

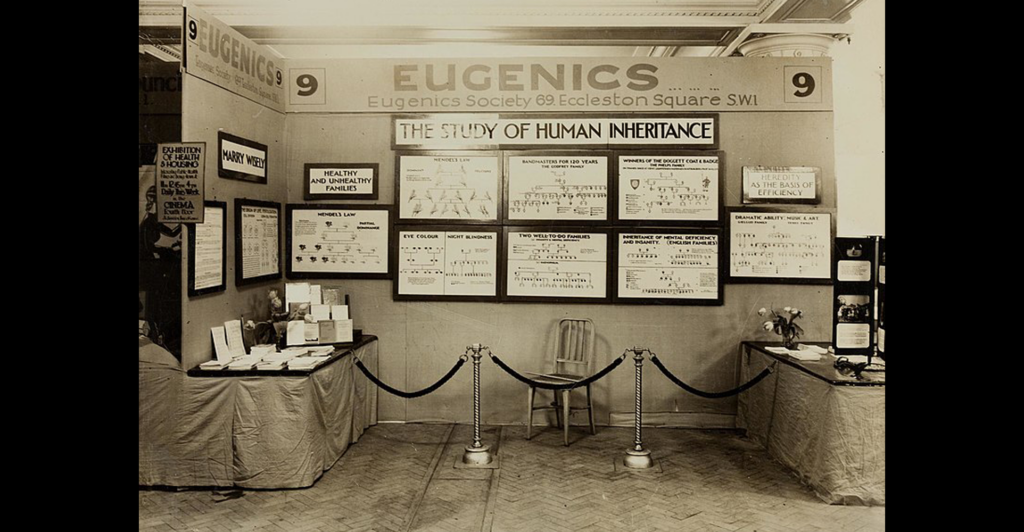

- Marnie Gelbart, Personal Genetics Education Project, pgEd: Gelbart’s session provided a brief overview of the history of eugenics, through a short clip from the Ken Burns documentary, The Gene: An Intimate History and pgEd’s curriculum on “Genetics, History, and the American Eugenics Movement”, which was reframed in the past 12 months, thanks to support from the NIH Science Education Partnership Award program. This lesson plan looks at the history of eugenics as a lens for examining recent advances in precision medicine and genome editing with an eye towards safeguarding against future injustices. pgEd has heard from educators across the country that this curriculum fills a content gap in the science classroom and gives teachers some of the tools required to feel confident in tackling a sensitive topic related to the misuse of genetic arguments. In the session, Gelbart presented pgEd’s recent work to reframe its curricula to center the people who fought back against racist and discriminatory policies and practices in genetics and medicine. This is part of pgEd’s larger efforts to truly integrate a broader spectrum of topics and include the experiences and voices of historically marginalized peoples into the biology classroom.

- Gregory Davis, Bryn Mawr College: Davis shared a vignette about an approach he has taken with students interested in the history of eugenics who’ve taken his undergraduate course in the history of genetics and embryology, which he teaches in the Biology Department at Bryn Mawr College. He focused on the advantages and caveats of co- and re-discovering the history of one’s own institution with students by examining primary sources—in this case, papers presented by both geneticists and eugenicists at the Second International Eugenics Congress in 1921.

- Michele Markstein, UMass Amherst: Markstein’s presentation focused on two approaches that she has used in teaching eugenics history to large undergraduate classes: (1) inviting her colleague, Dr. Laura Lovett from the History Department to guest lecture and (2) presenting the material herself in a blended approach that enables students to review scientific topics from earlier in the semester (e.g., pedigree analysis, DNA sequencing, SNP genotyping, pleiotropy, human evolution and migration) while exploring ethical considerations in deciding to eliminate a SNP associated with “pathogenic” body odor from the human population. At the end of this lecture, most students in her white-majority class learn that they likely have the “pathogenic” SNP. In Markstein’s experience, both approaches resonate especially well with Black and Latinx students.

- John Novembre, University of Chicago: Novembre’s presentation focused on teaching about the interface of genetics and society in a graduate curriculum. The importance of this type of teaching is supported from the National Academy of Science’s recent report on Graduate Education for the 21st Century, and he shared some of the practices he and his colleagues have been experimenting with at the University of Chicago. These include activities around teaching about genetics and race, as well as the history of eugenics. He concluded with sharing some challenges to this work and highlighting the need for more resources and educational research in this area.