Genetic analysis of an island population of mice reveals that 19 quantitative trait loci are responsible for their impressive size.

Island populations of animals, isolated from their mainland relatives, have given us insight into evolution from the very birth of the field. In fact, studying finches on the Galápagos Islands helped Charles Darwin establish his theory of evolution.

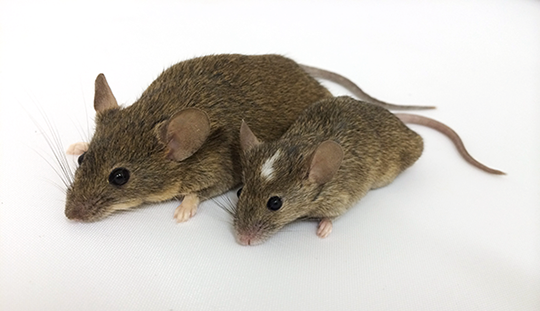

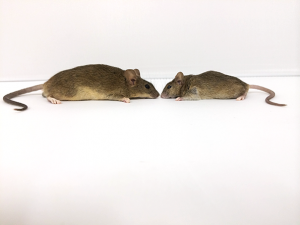

Today, with the genetic tools available to us, studying island populations provides mechanistic clues into how these animals evolve traits that distinguish them from their mainland relatives. Gough Island, a small, remote island in the South Atlantic, is home to the largest wild house mice in the world. These mice, which were brought to the island on seal fishing and whaling ships about 200 years ago, are often double the weight of mainland mice. Two hundred years is a short span on the evolutionary timescale – meaning that this adaptive size change happened in as few as 400 generations!

The mice on Gough Island are the same subspecies as laboratory mice (Mus musculus domesticus), which allows researchers to use well-established genetic tools to investigate their evolution.

In their recent GENETICS paper, Gray et al. report that 19 quantitative trait loci (or QTL) are responsible for the size difference between island mice and mainland mice. QTL are regions of DNA that influence a quantitative trait – a characteristic that varies along a continuous scale, such as weight. While each of the discovered QTL has a modest effect on body size, the sum of these effects across loci explains much of the size difference between island and mainland mice. This mode of inheritance contrasts with monogenic traits, which are controlled by single genes, and with traits that are controlled by a few genes with large effects.

Gray et al. discovered that the biggest difference in growth rate between island and mainland mice occurred in the first six weeks of life, with the island mice’s accelerated growth leading to the overall size distinction between the two populations. The rapid evolution of the larger body size in the novel environment of the island suggests natural selection is the primary force at work. Gough Island mice have fewer predators and less competition, and the removal of those selective constraints may also contribute to their ability to grow larger.

CITATION Gray, M.M., Parmenter, M.D., Hogan, C.A., Ford, I., Cuthbert, R.J., Ryan, P.G., Broman, K.W., Payseur, B.A. 2015. Genetics of Rapid and Extreme Size Evolution in Island Mice. GENETICS, 201(1): 213-28. doi:10.1534/genetics.115.177790 http://www.genetics.org/content/201/1/213.full