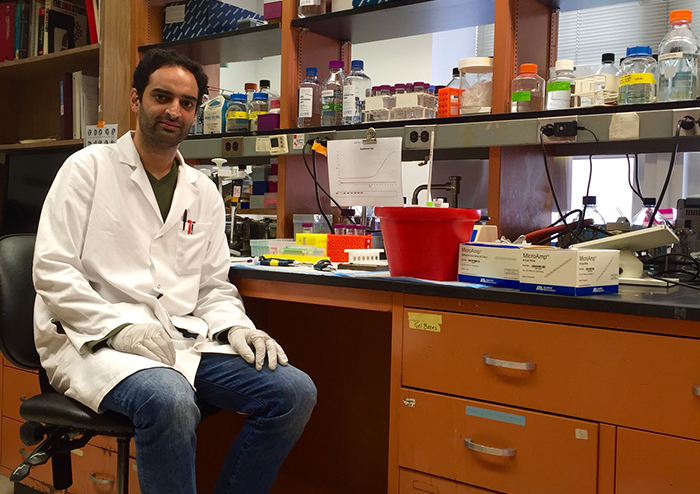

Interview with Aashiq Mirza, postdoctoral fellow at Weill Cornell Medicine, talks about acquiring interdisciplinary skills and practical habits for success during the early stages of a research career.

Interview with Aashiq Mirza, postdoctoral fellow at Weill Cornell Medicine, talks about acquiring interdisciplinary skills and practical habits for success during the early stages of a research career.

In the Decoding Life series, we talk to geneticists with diverse career paths, tracing the many directions possible after research training. This series is brought to you by the GSA Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee.

When did you know that you wanted to work in genomics and to become a scientist?

Initially, I wanted to be a medical doctor. I changed my mind as I was wrapping up my undergrad in biotechnology and human genetics. The major turning point was during my Master’s project in Human Genetics and Biotechnology in India where we looked at a particular loss of function mutation in a population. I was really intrigued how a single nucleotide change can lead to a dramatic and dreadful effect downstream. Of course, now I realize that it is not easy or straightforward… but that was it!

Do you ever feel that there is some additional training that you wish you had during your graduate and postgraduate stages?

Some programs allow you to spend one semester or six months in another lab across disciplines to promote multidisciplinary research approaches. This makes you a more well-rounded scientist and allows you to bring back new techniques or a new competence to your own lab and project. It also helps you network and broadens your horizon so you are not limited to learning only your lab’s techniques. It would have been really nice to have this type of exchange program during my training.

Science is changing at an amazing pace. What challenges and opportunities do you think this presents to you and your field, and how are you preparing for this new world?

Aashiq Mirza during a recent visit to his PhD lab at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

I am trying to catch up with new technologies and techniques by attending different seminars and workshops. Currently, sequencing data requires a series of preprocessing steps and analyses by bioinformaticians before it can be read by medical professionals. This is a major barrier for the clinical application of gene editing and personalized genomics. To overcome this challenge, it is important to build new interdisciplinary collaborations to deliver new knowledge and technologies to the clinic.

What are the top habits that you think are important for your success?

Sometimes I feel I am overstretched and over-committed. But I still devote every second day to run at least six miles, so it is important for me to manage my time efficiently. Because of this, I tend not to procrastinate or postpone things at work, which helps me be successful. I am also a firm believer in the dogma “someone helped me and I should pass it on to others.” I am always available for my colleagues and for my friends. Helping others helps us to be more successful.

From your experience, what professional skills are often undervalued by early career scientists entering the job search?

Sometimes we overlook the spirit of teamwork and work ethic. Intellectually, one can be fantastic and hard-working, with an impeccable publication record, but she or he may not be a team worker and that can be problematic for the lab. Poor communication skills and interactions can impact the project and the principal investigator. Instead of focusing on the science, they have to spend time figuring out how to sort out nitty-gritty routine things. It affects productivity and the project in the long run.

What are the most essential steps to prepare for finding a new training position?

Firstly, reach out to your mentors because the process of applying for a new position can be confusing. I was fortunate to receive advice from Maneesh Pingle, an assistant professor in our lab at the time. He helped me identify a graduate program that best fits my interest and he encouraged me to step out of my comfort zone and seek training in new settings and countries despite several hurdles.

Secondly, know the mission of the organization. You should not apply because the lab has a big name. It is very good to do your homework and see what they expect from you. Usually, these big institutes and research centers have mission statements on their webpage. You can benefit by checking to see if they align with your long-term research goals.

Thirdly, consider the project, its progress, and your interest. Sometimes certain research projects are not open-ended questions. If you are seeking a position where the project is almost complete, it will be in the last stages and you will be left with little potential. If, for example, you are looking for a postdoc position to eventually start your own lab, you would want something that has long-term potential.

Lastly, ask about the lab environment. You don’t want to be in a lab that has a good record and great publications if life is miserable and people are not happy. This is really important because it will eventually affect you.

What do you do for fun?

I have a keen interest in old antiques, and I spend some weekends strolling down flea markets and antique shops. What used to be a new technology just 50 years back is now in a museum. Time changes, and everything is dynamic. It keeps reminding me that nothing stays the same.

About the author:

![]() Faten Taki is the Liasion for the Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee and a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medical College. Her goal is to be able to give back to the scientific community while still growing as an early career scientist.

Faten Taki is the Liasion for the Early Career Scientist Career Development Subcommittee and a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medical College. Her goal is to be able to give back to the scientific community while still growing as an early career scientist.

Learn more about the GSA’s Early Career Scientist Leadership Program.