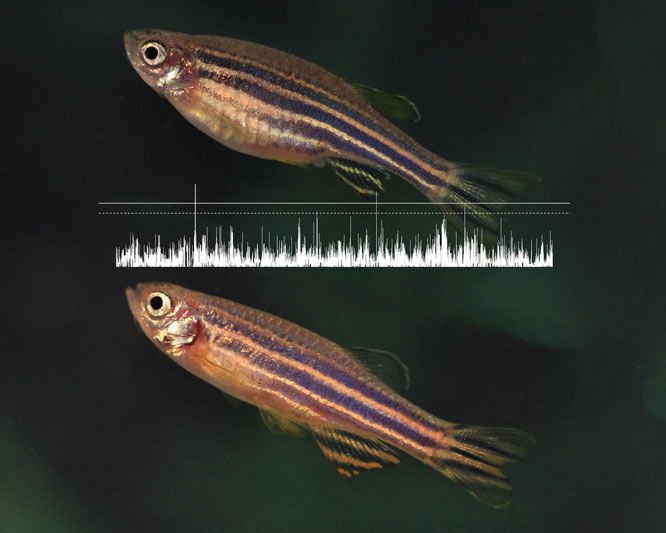

Laboratory zebrafish hide a dirty little secret. Although the tiny fish have proven to be a vital model of vertebrate development and disease genetics, zebrafish reproduction—at least in the lab—has wildly variable outcomes. Offspring sex ratios can vary from extremely male-biased to extremely female-biased, depending on which breeding pairs serve as parents.

The reason for this variability, and the basics of how zebrafish determine their sex, have remained a mystery for decades. The major factors affecting sex ratios in this species are genetic, but zebrafish lack obvious sex chromosomes, which in other species are often mismatched sizes. Several sex-linked loci have been located in zebrafish, but studies that used different strains identified different loci. One explanation is that zebrafish sex determination may be a complex, polygenic trait. The title of a recent review probably summarizes the situation best: “Zebrafish sex: a complicated affair.”

Now, a paper by Wilson et al. in the November issue of GENETICS has resolved a major source of the confusion by concluding that laboratory zebrafish strains lack the natural sex determination system of their wild counterparts.

The study, led by John Postlethwait of the University of Oregon, used the “RAD-sex” method to identify SNPs found more frequently in one sex than the other. In this approach, a genome-wide association study is used to compare genotype data from males and females derived from RAD-tags (restriction site-associated DNA tags).

The team verified that RAD-sex works by analyzing a fish species in which the sex determination locus is already known. But to their surprise, trying the same approach with the two most commonly-used zebrafish strains yielded no associations. None of the more than 30,000 tested SNPs were significantly associated with sex. In contrast, tests of the “natural” zebrafish strain included as a control revealed several strong associations, all mapping to the same 1.5 Mb region of the genome. These fish had spent only eight generations in the lab and had not been subjected to the intense selective breeding procedures used to establish true laboratory strains.

Suspecting that the discrepancy between the RAD-sex results was due to the difference between “wild” and “lab” breeding histories, the authors repeated the procedure with three more unselected strains derived from wild stocks. The results confirmed the location of the natural sex determination locus, and suggested that zebrafish use a sex determination system similar to that found in birds, in which females are heterogametic (heterozygous at the sex locus) and males homogametic.

So what happened to the lab strains? There’s not enough data to say for sure, but it seems likely that —independently in the two strains—domestication has disrupted the function of the natural sex determination system. After decades in culture, these fish seem to have developed or strengthened alternative methods for sex determination, relying more heavily on environmental and multiple weak genetic factors than their free-range cousins. With further study, lab zebrafish might even become a powerful model for the rapid evolution of new sex determination systems.

The results also remind us that evolution rarely stops, even in the lab.

CITATION: Wilson C.A., B. M. McCluskey, A. Amores, Y.-l. Yan, T. A. Titus, J. L. Anderson, P. Batzel, M. J. Carvan, M. Schartl & J. H. Postlethwait & (2014). Wild Sex in Zebrafish: Loss of the Natural Sex Determinant in Domesticated Strains, Genetics, 198 (3) 1291-1308. http://www.genetics.org/content/198/3/1291

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.114.169284