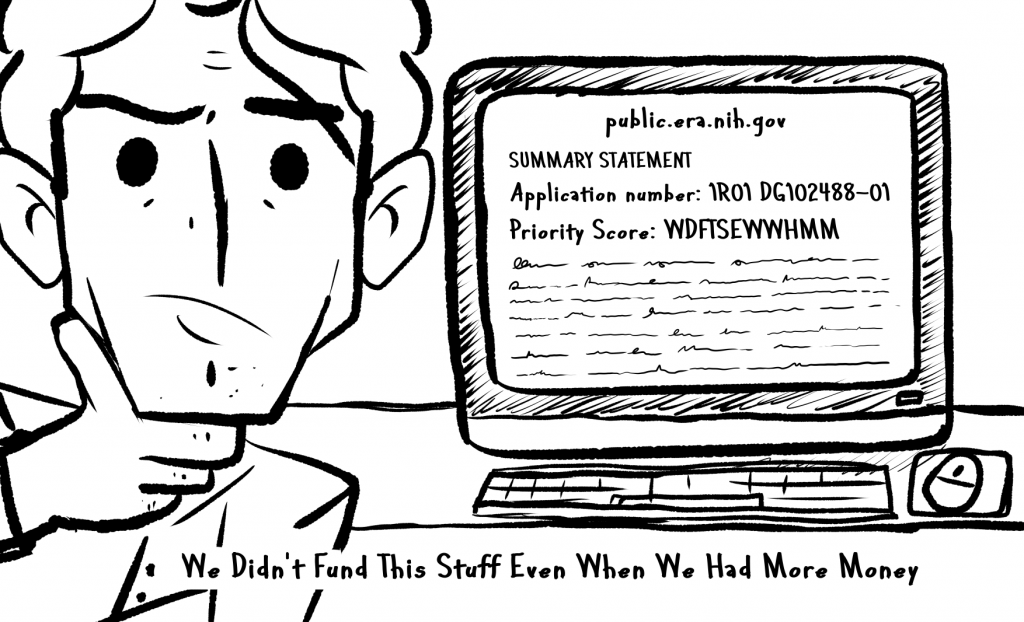

For an American biologist, submitting a grant application to the NIH may feel like buying a lottery ticket for Powerball. Or perhaps it’s more like the inside of the bottlecap that reads, “Each participant has a 1 in 250,000 chance of winning the big prize.” Yet there may be a way to make the likelihood of garnering an NIH grant much better. But I am going to need your help.

For an American biologist, submitting a grant application to the NIH may feel like buying a lottery ticket for Powerball. Or perhaps it’s more like the inside of the bottlecap that reads, “Each participant has a 1 in 250,000 chance of winning the big prize.” Yet there may be a way to make the likelihood of garnering an NIH grant much better. But I am going to need your help.

Perhaps you’re thinking that I have this wonderful elevator speech for us to give to our Congressional members, who will be so swayed by it that funding of medical research becomes their top priority. These members then get together and hugely increase the NIH budget (it did recently get a $2 billion increase, but that’s not huge, especially since the budget has been essentially flat for the past decade), and presto, our grant problems are solved.

That’s not gonna happen.

Instead, we need to follow the advice of the legendary thief Willie Sutton, who, when asked why he robbed banks allegedly replied: “Because that’s where the money is.” If we’re going to make getting a grant easier for the great majority of biologists—and with no additional big budget increases in the offing—then it seems obvious that we have to move the money from people who have a lot of it to those with not much of it.

One NIH institute, NIGMS, already has a policy that requires extra scrutiny and justification before investigators with total direct funding (including the pending award) of over $750,000 receive another grant; thus, this policy kicks in when an investigator with around $500,000 in existing direct costs applies for another grant. If the application under review is not deemed promising enough, then the grant is not awarded.

NIGMS seems to have a few rationales here. One is that the productivity of a typical researcher shows diminishing returns beyond direct costs of a few hundred thousand dollars per year (Lorsch 2015a). Another is that NIGMS feels that if they can support more researchers, the ensuing diversity in location, institution, people, organism, and approach is likely to lead to more breakthroughs. No one can predict who will make that stunning connection that opens up wide swaths of a new field. Those of you who are not well-funded and, after study section review, arrive at the borderline of funding, certainly appreciate when some well-funded investigator doesn’t become better-funded.

While not many investigators have a large amount of NIH funding, 5% of NIGMS grantees had 25% of NIGMS grantees’ total NIH direct costs, and NIGMS grantees with more than $500,000 in total direct costs held about $400 million of NIGMS funding (Lorsch 2015b). Because a similar pattern is true for the entire NIH, a substantial chunk of the whole NIH budget is held by a relatively small number of well-funded investigators.

We need a policy change so that the other NIH institutes work like NIGMS. Although the NIH as a whole has a council review policy that applies to well-funded investigators, it’s not nearly as stringent: it’s a $1 million threshold of active awards (i.e., not including the application being considered) and it excludes applications in response to RFAs and multi-project and multi-PI applications (unless all PIs are above $1 million). You could drive an 18-wheeler through these exceptions.

My well-funded colleagues seem to appreciate the purity of the NIGMS policy, as they refer to it as “pure [unprintable phrase 1]” and “pure [unprintable phrase 2].” They say it goes completely against the meritocratic vision of the NIH that has led to so much good science over the years. They say that those with a new idea to cure cancer, or AIDS, or Alzheimer’s, should get the money to do so, regardless of how high their current funding is or how much some scientist in [pick your favorite State that’s not on either coast] needs it.

But to be clear: I’m not advocating a “let’s look carefully” limit on anyone’s total funding—only the NIH portion of that funding. Investigators would still be free to pursue as many dollars as they like from the Gates Foundation, the American Cancer Society, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, or any of the many other organizations that support medical research. If they can amass millions of dollars of support from other funders for their research, we shouldn’t begrudge them their success. In fact, tough NIH scrutiny of well-funded investigators might provide them with a strong rationale to argue their case for grants from private organizations.

The idea for a universally-applied “extra scrutiny” policy at the NIH with real teeth is a simple one, but I doubt that a large fraction of NIH administrators will jump at the chance to potentially slash the funding of their most successful extramural scientists.

That’s where you come in. If you agree that we need such a stringent NIH-wide policy, write to the director or a program officer of the NIH institute where your grants are administered. And point out my post to your buddies in other fields—cancer, heart disease, infectious disease, neurobiology, etc.—who may not be geneticists but who struggle for grants just like we do. Ask them to write to the folks at the NIH institutes that they deal with. Maybe we can generate a groundswell of support for this idea. If we succeed, Robin Hood would have been proud of us.

CITATIONS:

Lorsch, J.R. (2015a). Maximizing the return on taxpayers’ investments in fundamental biomedical research. Mol. Biol. Cell 26(9): 1578-1582.

Lorsch, J. (2015b). More on my shared responsibility post. NIGMS Feedback Loop Blog, January 12.